Choose A Norwich First

1770s First Doctor To Tie Femoral Artery

1772 First Cut-Nails in America

1781 First President of the United States

1792 First Turnpike in New England

1818 Stars & Stripes US Flag Design

1826 First Use of ‘Hello’ in Print

1843 First Patent Printer Invented

1845 First Mechanical Chirographer Invented

1854 First Lever Action Gun Invented

1854 First .22 Caliber Cartridge Bullet Invented

1857-1858 Window Blind Staple Patents

1899 First Standard Croquet Rules in America

1902 First Hydraulic Compressed Air Plant

1910 First Triplane Built in America

1937 First National Apprenticeship Legislation

1963 Werman's Shoe Patents

1680 Bean Hill Pottery

“At Bean Hill was one of the first potteries in this country. They manufactured a yellow brown salt-glazed earthenware, of which there are a very few specimens in existence. This salt-glaze was discovered about 1680 by a servant who lived on the farm of a Mr. Yale. There was an earthen vessel on the fire with brine in it to cure pork. While the servant was away the brine boiled over, the pot became red hot, and the sides were found to be glazed. A potter utilized the discovery and the salt-glaze became an established fact.”

Excerpt from Info Source 1

Acknowledgements

“Norwich Early Homes and History”, page 19, (1906), by Sarah Lester Tyler

Chipstone – by John Swann

1770s First Doctor to Tie Femoral Artery

Dr. Philip Turner, a native of Norwich, was the first surgeon in America to perform an operation that included tying the femoral artery. He was a surgeon in Norwich who also served in the Revolutionary War as a military surgeon

The image on the left illustrates the location of the femoral arteries. The iliac artery sends blood to the lower part of the tummy and splits to form the femoral arteries above the groin. This femoral arteries deliver blood to your legs. Lower down the leg, the femoral artery itself splits into other arteries that send blood to the lower leg.

The femoral artery is the primary source of blood in each of your legs. Thus, when a traumatic leg injury that results in excessive bleeding, the femoral artery must be temporarily tied (i.e. clamped) closed. After the surgery is complete the artery is untied (i.e. reopened).

Dr. Turner’s home, at 29 West Town Street is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Acknowledgements

“Norwich Doctor 1st to Tie Femoral Artery in 1700s“, (09/11/2017), by Richard Curland

1772 First Cut-Nails in America

Bean Hill was the home for several early craftsmen and artisans. According to the Info Source, Edmund Darrow was a Bean Hiller who produced America’s first cut nails.

“Early industry did not attain any importance until 1772 when a Bean Hill blacksmith, Edmund Darrow, produced from barrel hooping the first cut nails in America.” — Excerpt from Info Source 1

“Another important enterprise was the manufacture of cut shingle-nails from old iron hoops, which was commenced in 1772, and continued during the war, by Edmund Darrow. This naillery was not large, employing only from four to six hands, but was a great convenience to the community, and merits notice from its being one of the first attempts in this country to make nails in a way less slow and tedious than the old operation of hammering them out of solid iron.” — Excerpt from Info Source 2

Nails have been in use since the beginning of the Bronze Age, (circa 1800 B.C.). From that time until nearly 1800 most nails were made by hand at a forge. Due to the need for thousands of nails to build even one wooden building, this was an arduous, time-consuming process. The top image illustrates a typical hand-wrought nail produced prior to 1800.

The time required to produce nails was dramatically reduced when manufacturers learned how to cut the nails. According to the Info Source, in 1772, Edmund Darrow cut his nails from barrel hoops. Most likely the cutting process was done by hand, not machine. The process was certainly faster than forging nails, but, a more efficient process was needed to increase the speed of production.

The first nail cutting machine in America was patented on March 23, 1794 by Josiah Pearson of New York. Between the years of 1794 and 1817 more than 100 patents were issued for nail making machines. The second and third images illustrate examples of a cut-nails made from one of these early machines. The bottom image illustrates a modern, wire nail.

Nails provide one of the best clues to help determine the age of historic buildings, especially those constructed during the nineteenth century, when nail-making technology advanced rapidly. Until the last decade of the 1700s and the early 1800s, hand-wrought nails typically fastened the sheathing and roof boards on building frames.

Between the 1790s and the early 1800s, various machines were invented in the United States for making nails from bars of iron. The earliest machines sheared nails off the iron bar like a guillotine.

Acknowledgements

“The WPA Guide to Connecticut: The Constitution State”, (2014), page 325

“History of Norwich, Connecticut: From Its Possession From the Indians, to the Year 1866”, page 372, by Frances Manwaring Caulkins

“Nails: Clues to a Building’s Age”, by Thomas D. Visser

The complete list of sources may be found by clicking the “Bibliography” button, and, then typing “Darrow” in the SEARCH box.

1781 First President of the United States

Samuel Huntington signed the Declaration of Independence and was a founding father of the United States. Some historians consider him the first President of the United States.

He was elected to the Connecticut Legislature in 1764, and eight years later, was made a judge. After being elected to the Second Continental Congress in late 1775, he took his seat early the next year. He represented Connecticut in the Second Continental Congress from 1776 to 1781, serving as President of the Congress from September 1779 to July 1781.

When the Second Continental Congress convened, it was the first time that representatives from all thirteen colonies united together as a single group of united states. During this congress the nation’s first framework of government, the Articles of Confederation, took effect on March 1, 1781. Since Huntington was President of this Congress, he has been called the first legitimate President of the United States.

When the Second Continental Congress convened, it was the first time that representatives from all thirteen colonies united together as a single group of united states. During this congress the nation’s first framework of government, the Articles of Confederation, took effect on March 1, 1781. Since Huntington was President of this Congress, he has been called the first legitimate President of the United States.

Acknowledgements

“Huntington A Forgotten Giant in American History”, 07/13/2008, by Bill Stanley

SamuelHuntington.org

The complete list of sources may be found by clicking the “Bibliography” button, and, then typing “Samuel Huntington” in the SEARCH box.

1792 First Turnpike in New England

The Norwich – New London turnpike was the first operational turnpike in New England and the 2nd in the United States (Info Source 1). The turnpike was originally called Mohegan Road and is now a part of modern-day Connecticut Route 32.

The article below is an excerpt from Info Source 2. It states that the Norwich-New London turnpike was the first turnpike in the United States. However, it is actually the second.

“The first road between New London and Norwich was laid out by order of the Legislature in about the year 1670, but for more than a century, however, the road was little better than an Indian trail.”

“In 1789 several prominent individuals formed an association to effect an improvement of this road. The Legislature granted them a lottery, the avails of which were to be expended in repairing so much of the road as ran through the Indian land. This lottery was drawn at Norwich in June, 1791. The next May a company was incorporated to make the road a turnpike and erect a toll-gate. By these various exertions the distance was reduced to fourteen miles from the court-house on Norwich Green to the court-house in New London, and the travelling rendered tolerable safe. The toll commenced in June 1792 [4-wheel carriages, 9d. (i.e. 9 pennies) ; 2 do. 4½ d. ; man and horse, 1d.].”

NOTE: The abbreviation “d” for penny, came from the Latin word penny “denarius.”

The 1791 Washington Penny, shown on the left is worth about 27¢ today (excluding its numismatic value).

The pennies were made of copper. After they turned red (due to its copper content). One penny was called “One red cent”.

This was the first turnpike in the United States. Dr. Dwight observes in his “Travels” that this road brought the inhabitants of Norwich and New London more than half a day’s journey nearer to each other. “Formerly (he says) few persons attempted to go from one of these places to the other and return in the same day ; the journey is now easily performed in little more than two hours.”

“This turnpike became almost immediately an important thoroughfare, of great service to Norwich and the towns in her rear for driving cattle and transporting produce in New London for embarkation. In 1860 it was extended to the landing by a new road that began at the wharf bridge and fell into the old road south of Trading Cove bridge. In 1812 another new piece of road was annexed to it, which was laid out in a direct line from the court-house to the old Mohegan road. The company was dissolved and the toll abolished July 1, 1852.”

Acknowledgements

Oldest.org

Professional Coin Grading Service (PCGS)

1818 Stars & Stripes US Flag Design

Designed by Samuel Chester Reid

After the War of 1812 Captain Samuel Chester Reid, a native of Norwich, designed a new U.S. flag. In January 1817, Reid was asked by U.S. Congressional Representative Peter H. Wendover for advice in the design of a new U.S. flag. The existing flag design had fifteen stars and fifteen stripes. The design had not been updated to reflect the five new states which had joined the union since that version of the flag was implemented in 1795.

Reid and Wendover decided that the best way to honor all twenty states was to restore the number of stripes to the original thirteen, have twenty stars on the canton and add a new star each time a new state joined the union. Reid submitted the flag design (shown above). This flag had 20 stars, one for each state, and 13 stripes, one for each of the original 13 colonies.

A bill was adopted in the U.S. Congress which stipulated that the thirteen-stripe, twenty-star design become the new official flag of the United States. The bill passed and was signed into law as the Flag Act of 1818 by President James Monroe on April 4, 1818. On acceptance of the design by Congress, Captain Reid’s wife made the first new flag with silk provided by the government. It was flown from the Capitol dome on April 13, 1818.

The pattern of the stars was later changed from Reid’s “great star” design to four rows of five stars each. However, the concept of retaining the 13 stripes for the original 13 colonies and adding a star for each new state is still used today. The most recent change to the flag was in 1960 when the number of stars in the flag changed from 48 to 50 when Hawaii and Alaska were added to the United States.

Acknowledgements

“Flag: An American Biography”, (2006), by Marc Leepson

Wikimedia Commons

The complete list of sources may be found by clicking the “Bibliography” button, and, then typing “Samuel Chester Reid” in the SEARCH box.

1826 First Use of 'Hello' in Print

Hello!

Yes, we have all said it a million times. But … when, where, and what context did ‘Hello’ first appear in print? The Oxford English dictionary attributes the first use of ‘Hello’ to the October 18, 1826 edition of The Norwich Courier, a weekly newspaper published in Norwich from 1796-1845. The image shown on the left was created directly from microfiche from the 10/18/1826 Courier article.

The reproduction, shown on the left, is an excerpt from the complete article. The article retells a humorous prank that a young lad tried to play. The word printed in the original Courier article is ‘Hollo’ not ‘Hello’. But … ‘Hollo’ is certainly used here in the same context as the word ‘Hello’ is typically used today.

The Oxford English dictionary says that the word ‘Hello’ is a descendant of the word ‘Hallo’ which in turn is a descendant of the word ‘Hollo’.

After reading the article, you might also wonder what a ‘plaguy’ Methodist is. Dictionary.com defines “plaguy” as: annoying, bothersome, burdensome, disagreeable, disappointing, nagging, nettlesome, pesky ….

*Place cursor over map to magnify

Acknowledgements

Wikipedia

Norwich Courier (08/18/1826)

Bob Dees

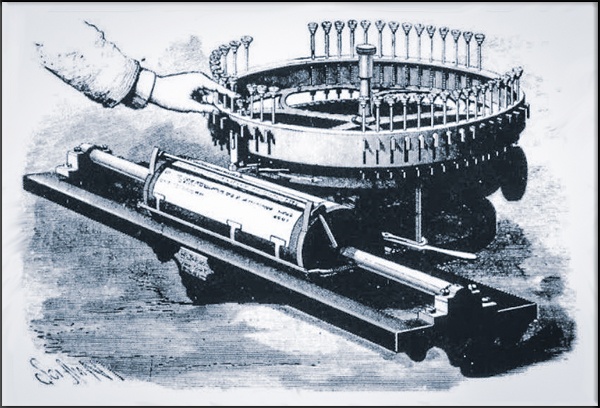

1843 First Patent Printer Invented

The image shown above illustrates the “Patent Printer”. Charles Thurber patented this machine in 1843 while in Norwich. It was the first of four patents that he obtained on various “writing machines”. The Patent Printer patent is regarded as one of the first patents associated with the typewriter.

Charles Thurber, a Norwich resident from 1842-1847, was an inventor, and could be considered a Renaissance Man. During his lifetime he: a) Was a Latin school teacher, and b) the principal of a Latin Grammar school, and, c) invented four different typewriter models, and, d) Along with his partner, Ethan Allen, established and operated the Allen & Thurber, manufacturing facility in Norwich.

Acknowledgements

OzTypewriter.BlogSpot.com

Scientific American, April 30, 1887

“Antique Typewriters (From Creed to Qwerty)”, (1997), by, Michael Adler

The complete list of sources may be found by clicking the “Bibliography” button, and, then typing “Patent Printer” in the SEARCH box.